Agricultural industrialisation, growth and degrowth

Why can't we return to the shire? Also, a defence of the centre pivot.

This is a wide ranging post that develops some of the ideas contained in my past work on agricultural complexity. This is a topic I’m working on as part of a broader research effort on the catastrophic risks of losing sections of civilizational complexity. One day this will be spun into publications and more concrete outputs, however this post is primarily for background on the topic. Agricultural processes can optimise for many things, and it’s a common newcomer trap to assume that output per hectare is the most important. This post maximises anecdotes per hectare.

This analysis is in progress, and deals with complex systems. All words are my own unless otherwise indicated, alongside all mistakes.

There’s an old story that a frog jumps out of hot water, but will calmly sit in a pan brought slowly to the boil. This isn’t true, and frogs aren’t that stupid, but it’s an attractive meme for the truth it captures: viewing changes from within can be deceptively hard, and a rapidly shifting normal can catch us off guard.

Here’s a graph of economic growth over the last centuries.

Living in the moment, it can be really easy to forget just how strange our times actually are, and how rapidly things are moving worldwide. Our lives are sharply different to those of our grandparents, and our children will almost certainly see sharper changes still. This process is happening worldwide: billions are entering middle income bands, and the average experience of a human on this earth is radically different from those of past decades, let alone centuries.

There are many elements to this story, but one key dynamic has been the move away from the rural for the first time in human existence. Prior to the industrial revolution something like 80-90% of the population of most settled agrarian states were engaged in farming and other rural activities1, and this has been pretty reliable throughout our history. More broadly, hunters, gatherers, pastoralists, nomads and agrarians all needed the majority of their working populations securing food during at least the peak times of the year, and this defined the human experience.

Traditional rural life was far from simple, and involved developing a range of skills across many different areas, which were not limited to growing food. For agrarian societies these included cultivating fields, herding animals, managing orchards and forests for food and fuel, making cloth and clothes, crafting tools, building fences, roads and structures, hunting and fishing (though almost always with restrictions) as well as periods of travel, trade and seasonal labour.

Farmers harrowing, sowing and guarding a field from magpies. There’s even a scarecrow bowman in the middle.

Some feel this traditional agrarian life was idyllic2, as we’ll talk about later, and it certainly wasn’t terrible for most. However, it certainly does limit you. Even with simple animal power you’re still working hundreds of hours to produce a tonne or so of food, worth a few hundred dollars in modern money. This sharply limits how many things people can do other than farm, imposing a hard limit on human flourishing. It also really sucks for those who want to do something other than farm. People lived in these ways due to necessity, and when you’re on a few hundred dollars equivalent you don’t have that much room for self actualisation.

It is also a real issue for those who want access to things like modern medicine, household labour saving technologies and mass transportation, all of which cannot be supported on such a narrow surplus. Quality of life isn’t linearly related to GDP per capita by any means, but it is certainly linked, and below ~$10,000 per person per year countries struggle to provide modern healthcare, schooling and sanitation for their populations, which is out of reach for smallholder farmers.

The correlation between the percentage of the labour force in agriculture, forestry and fishing versus a country’s productive capacity in the modern world is clear (see the diagram below). This causality does go both ways, and having only a small percentage in the sector is no guarantee of wealth. However, having a workforce over 10-20% in the sector is a clear indicator of modern poverty, and no country has reached developed status without flipping the historic ratio on its and ending up with 90% of their populations not in agriculture, forestry or fishing.

Global GDP per capita vs % of labour force in agriculture, forestry and fishing, 2021

Source: FAOSTAT

Overall, in order to move people out of the fields you need a few things:

More food per unit of land. This we got through better land management, fertilisers, crop protection chemicals, irrigation and seed breeding. Progress was made here prior to the industrial revolution, with cereal yields doubling from around 0.5-1 tonne per hectare to 1-2 tonnes in higher intensity areas that could access fertilisers. Nowadays the best areas now reach 10+ tonnes, while the physiological limits of most grains are around 20 tonnes per hectare. This gives us an eventual ceiling for yields, at least until we edit photosynthesis itself, however the global average is still around 4.2 tonnes: we have lots of room left to grow.

Fewer farmers needed per unit of land: This we got first by adding animal power, reducing the hours needed to hoe a field from 100-180 hours to around 30-40 via a plough. Mechanisation improved on this further, with now just an hour or so needed to plough a hectare.

Albert Rigolot’s 1893 “The Threshing Machine” - the amount of land feasible to farm with a set number of workers was historically constrained by the peak times: planting and harvesting, where you have a set window to get the crop into the ground or out of it before it spoils. Prior to animal power, preparing the ground with hoes was the most common bottleneck, after animal powered ploughs it switched to harvesting and threshing grains. As a result, early mechanisation initially focused on the harvest, with threshing machines and later combine harvesters to allow small teams to bring in and process a far wider area.

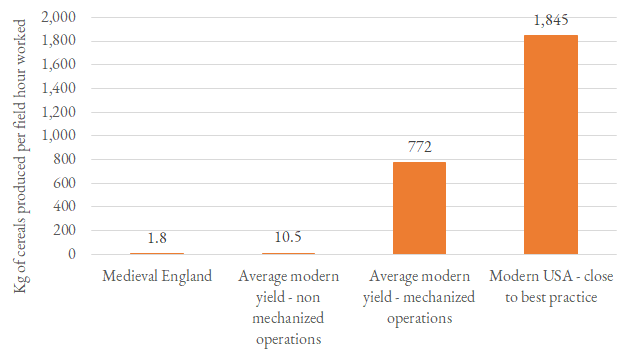

The shift can be hard to visualise, so here’s a rough estimate of how many tonnes of the big three cereal grains (wheat, rice and maize) were produced per average hour of labour since 1961. I also put Medieval England on there (coming in at around ~1.8 kg/hour) as a benchmark for a fairly high productivity historic farming system in terms of grain per hour (total yields in Asia were higher, but at the price of far more labour per unit area and unit of output).

Source: Energy and Civilization, FAOSTAT, author’s calculations

That gives some idea of how much productivity has risen. However, the graph above still doesn’t capture the full gulf, given that it is an average and significant parts of the world are still not mechanised or optimising fertilisers. So here is a second one, I had to add labels this time to make it even passably readable:

Make no mistake, this is a revolution: mechanisation of agriculture underpins our modern world, and without it the vast majority of our lives would still be tied to the land. It made the industrial revolution possible, with countries shifting their populations into factories and using the output to purchase foods produced using labour saving technologies, often from great distances. This has had profound impacts on our cities, culture and planet: moving us from a rural world based around a dense patchwork of small plots, to one based around wider fields and vast cities.

Largest cities in the world by year. Source: Chandler, Tertius - Working out the demographics of ancient cities is not easy, and there’s significant uncertainties of the exact totals. However, the inflection point is unambiguous. Cities are marked for the first time they appear in the dataset.

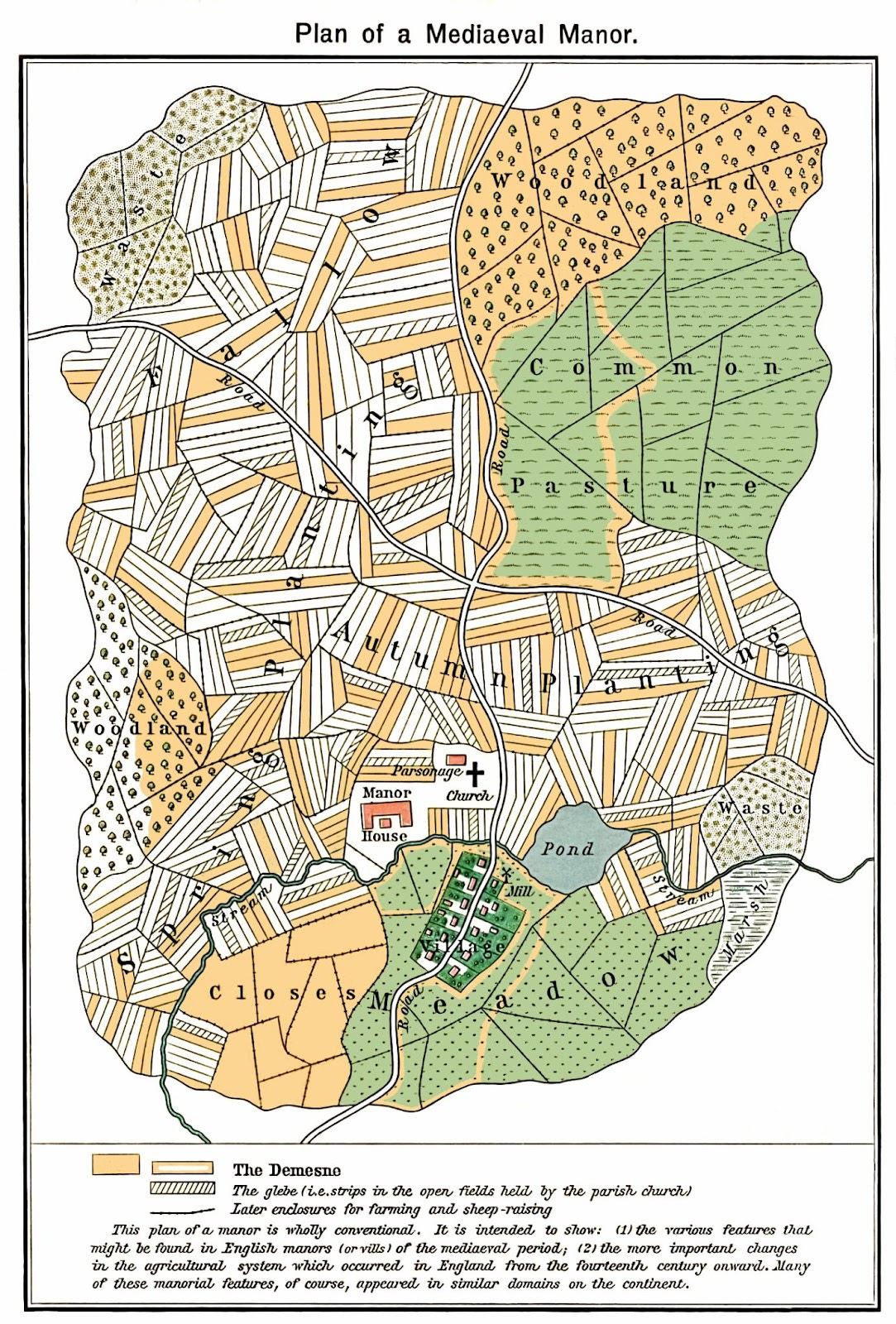

Map of a typical English manor from the 14th century. Note the mix of land uses, croplands in narrow strips (spreading the risk of losing a certain area between many crops and households), areas for grazing animals and managed woodlands for fuel. There were also very many different ownerships and claims (split between the lord (his demesne or later domain), church and peasants, though guess who did the actual farming). Changes to property rights and making things legible to outsiders was a big part of the industrial revolution too, for better or worse.

Centre pivot agriculture in Kansas, USA. Centre pivots are the most capital efficient way of irrigating land (although they are less water and land efficient than other systems), as rather than requiring full spraying infrastructure in each field you only need a rig that can be moved from field to field and then spun. The smaller ones here are 800m across (around 50 hectares) and the larger ones are 1600m across (200 hectares), meaning that even the smallest single pivot plot would have needed 10-20 people minimum to cultivate prior to mechanisation, and likely more. These fields would be impossible to manage without mechanisation at this density, as well as needing fossil fuels for fertilisation, transport and the majority of irrigation water pumping. While it’s hard to exactly pin down, the entire manor plot in the previous figure would likely fit in one of the bigger pivots here.

Degrowth, by choice

With changes as large as these, there are reasonable concerns to raise with modern input intensive farming. These are not trivial, and range from things like soil compaction and erosion, to the overworking of land causing a loss of fertility, pollution from runoff, a reliance on fossil fuels, carbon emissions, deforestation and more.

The good news is that solid progress is already underway on these metrics. In particular, changes to farming techniques (including precision farming, which carefully applies only the needed fertilisers and pesticides, doing far more with less) are both better for the farmer’s margins and the environment. Meanwhile, poor policies that encouraged massive oversupply of certain crops rather than balanced stewardship have started to also change, with farmers being paid for the work they do to manage their land rather than just to squeeze out every unit of output. All good stuff.

However, these proposals fundamentally come from within the system, and implicitly accept industrialisation and the changes that came with it as a framework. Naturally, there is also another position, based on an appeal to tradition: that the solution isn’t better policies or higher tech solutions, it’s active degrowth and a return to the fields and organic practices. This is laid out in reasonably well selling books, academic publications, as well as many academic journals, which all reject industrial agriculture as a paradigm.

For example both books linked above (“Sitopia” and “The Agricultural Dilemma”) propose something very radical: a fundamental shift in our agriculture back to pre industrial eras, shifting to smallholder farms, undoing globalisation and removing most or all synthetic fertilisers and chemicals.

What would happen if we did go ahead with degrowth voluntarily? Could we draw down mechanisation and artificial fertilisers, return people to the fields and keep the good of modernity while losing the bad? I’m still writing a paper partially on this issue (it’s more on the catastrophe side, for reasons that are about to become clear), however, it is fairly clear what the answer is:

Areas of the world with these kinds of food systems today struggle with food security, are almost all net food importers, and have a level of income where many services such as access to medicine are restricted. That’s not a great initial sign.

Countries with highly mechanised field operations would need to raise their workforces in agriculture many times over. Even if this was possible, large areas in certain countries would still need to be abandoned, as they are not viable under smallholder systems (most of Canada’s land and much of the USA and Australia for example).

This shift would mean far more people would be working in order to produce far less output, dwarfing any cost savings from the lower needs for machinery and chemicals. This is by definition a huge recession. It’s hard to pin down exactly how bad this would be, but to take an important example in the United States this shock would range from “similar to the great depression but forever” extending to “a significant loss of all industrial technology”. There are complex second order impacts, but these mostly look bad too.

A large proportion of the global population would need to move to small villages, and a large number of new dwellings would be needed for this new population to live and work on the fields, at very least on a seasonal basis. This would not be quick or easy.

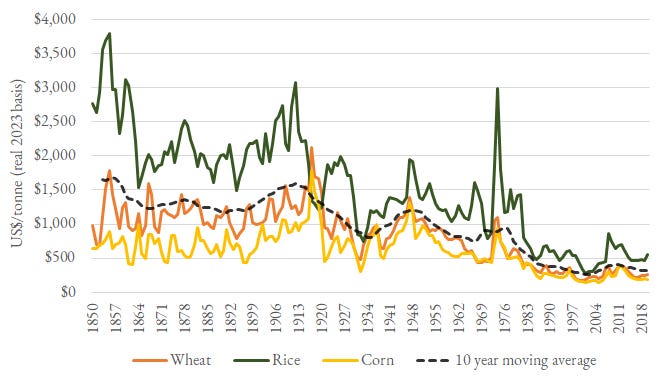

Food prices would rise sharply in this scenario, potentially by a factor of 3-5 (I’m still running these numbers, but food prices in real terms were much higher prior to the 1900s). This would kill many people by default, mostly lower income urban consumers in food importing countries, with Africa particularly exposed to this dynamic.

Source: Our World in Data, World Bank Pink sheet, author calculations. Real food prices have fallen steadily following the intensification of agriculture, and the actual decline for the consumer has been even sharper due to declining transport costs and tariff barriers. Higher food prices kill people, and cut access to vital necessities like medicine and education by eroding purchasing power.

Carbon emissions would fall from lower diesel use in the fields and lower fertiliser use, and emissions as a whole would see wild changes from the shock to GDP. These are nearly impossible to exactly measure, but emissions overall would likely drop due to the fall in GDP and deaths, assuming the degrowth is widespread. However, land use may rise, leading to habitat destruction, and lower income consumers may be forced to return to coal or wood for fuel to survive, further impacting the environment and health.

Source: Our World in Data. Another great chart from Our World in Data - charting the land use per person over the long run. Many I speak to assume that this curve is actually the reverse of its real shape, and that land use per capita today is far higher than in the past. If that were the case, degrowth would certainly be more viable. In reality moving left along this curve with 8 billion people would not be good for the environment, or the people.

Agricultural land use would rise significantly in an optimistic scenario where most people survive, as more land would be needed to meet the same without synthetic fertilisers, and manure supplies would fall due to animal numbers being cut back, by necessity if nothing else. This would be made even harder due to the need to meet fuel needs. In a pessimistic scenario land use is more ambiguous, due to the need to balance the deaths against the rising land requirements per hectare.

Source: Energy and Civilization, FAOSTAT, author calculations. A curve of cereal yields since 1961, versus an estimate of the same with synthetic nitrogen fertilisers removed. The real shock of stopping all chemical fertilisers and crop chemicals would be higher, as this is just the impact of synthetic nitrogen. Furthermore, the lower curve here assumes we can source the same amount of manure under a fully organic system, which is uncertain given that many cattle are fed on feed reliant on fertilisers, and grazing lands would need to be cut sharply anyway. Moving to the lower curve would kill people, and this is the case for all pure organic farming proposals.

Future economic growth would sharply reduce. Growth isn’t just new mobile phones (although these are useful), growth is also rising efficiency, better life expectancy, and everything we need to build the future. Being stuck halfway, unable to develop new technologies to manage or reduce carbon emissions but still making them would be a clear disaster.

It is hard to see how this degrowth could be voted for and maintained by democratic governments in the face of its manifest impacts. Non democratic ones would likely also struggle. This is some source of comfort in the face of the proposals.

The collapse in GDP would make countries adopting these measures unable to meet current defence commitments, meaning any adversary that did not follow would gain a decisive strategic edge. A consideration like this may seem foolish, but the ability to muster military force was the reason that GDP was first compiled. Recent events should have reminded the world that such considerations remain.

This is a cure clearly worse than the disease, and while the excesses and impacts of industrialised agriculture need to be seriously considered, a sensible plan would look at efficiency, land management and effective mechanisation. It will not contain degrowth.

I’m an economist, so I end up talking about efficiency, costs and land pressures, while for others these issues of food can reach into the sacred and the profane, raising the risk of talking past each other. How can the costs, prices and yields of crops matter when there are those that are starving people, when we’re polluting, when our very lives have changed unrecognizably.

However, I bring up costs precisely because of these factors: increasing the price of foods will kill people, lowering yields will force us to cultivate a far larger area and deforest even more, and we need to look at what we gained from industrialization, not just an imagined past of what we lost. I’m all for a talk about the externalities of farming, but those externalities are not a blank cheque, and the head needs to enter the picture.

We need to meet everyone on the planet’s needs for food, energy and a fulfilling life, and for that we need every tool we have, and then more. I’m a “energy too cheap to measure” kind of guy, and I hope that one day sustainability will be measured in the fraction of a dyson sphere that we require to maintain it.

However, even if you’re not that optimistic, the clear answer is that sustainability lies ahead of us. Hannah Richie laid out a pretty convincing argument that we have never been sustainable as a species by most reasonable definitions, and I agree. To get to sustainability we’re going to have to do something that has never been done with technologies that do not yet exist, and returning to an imagined past is a dead end.

If you want to homestead, go for it, and some people do love the life. However, it’s not for everyone, and I do note that the youtube videos of people who have done so still seem to buy their bulk calories: growing and pickling vegetables is fun, threshing wheat isn’t.

Some wish we had never industrialised, some wish that we never adopted agriculture. However, we did, and we have to deal with our reality, not wishes.

There are of course very different forms of living other than agrarian systems, like pastoralists, or hunter gatherers. I’m focusing on agrarians here due to the greater caloric density and thus populations they can achieve, which will be rather important in a moment when we discuss the possibility of degrowth combined with 8 billion people.

Very interesting data-driven post Mike. It reminded me of this good one: https://www.monbiot.com/2023/10/04/the-cruel-fantasies-of-well-fed-people/

**The below is no longer endorsed, these people apparently do exist in numbers**

However, one important weakness I saw is that it's very one sided and generally fighting a bit of a strawman. You look at what would happen if humanity was to return to medieval agricultural yield levels. I find that no group of people in the world is actually arguing for this. My impression is that there are two big camps on this end of things, arguing for very different things:

- Camp 1 is the groups of people (e.g. anarchoprimitivists) that propose that humans lived a more natural and happy life as hunter gatherers and therefore that is the state we should return to, by ending farming altogether and reducing the population of the planet by many orders of magnitude. The bases of this claim are hotly debated but in good part debunked, even by notorious proponents of related ideologies: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ted-kaczynski-the-truth-about-primitive-life-a-critique-of-anarchoprimitivism - Although some opponents do admit that the advent of agriculture may have made people's lives worse for a considerable period of time, compared to hunter-gatherer baseline - see https://www.cold-takes.com/has-life-gotten-better/

All in all, not really a serious alternative, but one that still capture some segments of popular imagination. But not at all arguing for returning to medieval agriculture.

- Camp 2 is more serious, we're talking about the people generally advocating moving to *regenerative agriculture* away from high-yield industrial agriculture. This is the group that the first article I linked to specifically critiques. This type of lower yield, higher sustainability agriculture is based on small farms and gardens is often based on philosophies like permaculture, agroecology, agroforestry, restoration ecology, keyline design, and holistic management. Some of them are not even against mechanization in agriculture as along as it is done sustainably and using techniques that are not fossil-fuel intensive, working at the interface between precision agriculture and regenerative agriculture. You can find plenty of examples from a quick google search but here's one as a sample: https://www.theengineer.co.uk/content/opinion/comment-four-ways-technology-is-driving-regenerative-agriculture/

I argue that the post would be seriously improved using baseline yields of regenerative agriculture systems as the comparison, as opposed to preindustrial yields. I think the story would play out similarly, but it would be a more realistic, fair and useful comparison. I'd argue these are the real-world "opponents" of the ideas you defend in this post, and as such it would be more useful to write posts like these in conversation with their ideas, instead of with the idea of returning to medieval agriculture which as far as I can tell nobody is arguing for- a strawman makes for an easy fight.

Nice summary Mike. However, it feels to me a bit like a strawman of degrowth. The argument you seem to make is: "Degrowth wants us to completely stop modern agriculture and this would be really bad."

The way I have understood degrowth so far is more in the way of doughnut economics. So, mainly making sure that we don't overstep planetary boundaries, while working on a more equal distribution of resources and not a complete abolition of agriculture.